John is my golf instructor. I came for help with my slice. He put my swing on the computer and compared it frame-by-frame with Ernie Els’ swing. Guess what? Els swing looked a lot better than mine! John showed me how I had a bit of a loop in my back swing and came down a little over the top and my hips turned too soon and my club got a little stuck behind me and also I didn’t stay behind the ball enough. See how Ernie does it? He then got onto the mat and started to show me these dynamics himself, all the while talking about angles and lag and X-factors and downward strikes and ball compression, and, interspersed with all this, mentioning that Sergio had incredible lag, how Hogan fought the dreaded duck-hook all his life and so weakened his grip like so, and that Tiger had shortened his swing for more accuracy.

John wouldn’t stop talking. 15 minutes into my ½ hour lesson I now knew several things: 1) my swing sucked, especially compared to Ernie’s, 2) there were lots of things wrong with the mechanics of my swing, all of which John immediately saw and understood completely, and 3) John knew a lot about golf and the history of this game. He taught me some drills that were somewhat useful, but I left the lesson not quite sure how to practice, what a good plan might be for my development, how to sense whether or not I was doing it right without someone watching, and what I should infer from bad outcomes.

Still, despite my reservations, I came back for a second lesson. I told him that I was working on one of the things he mentioned–taking the club back on an inside path–and that while I thought I was successful, my slice remained. He watched me take a few swings, put them again on video, and analyzed for me what he saw. It looked like I was still taking the club back a bit inside, encouraging an over-the-top downswing. However, John then made a series of other observations about my swing mechanics, many of which echoed those of the previous week, others brand new. It became clear that he didn’t quite remember our prior lesson, that we were, in effect, starting again from scratch. I realized then that since there were apparently so many things wrong, there would always be something to pick out to fix. The pattern repeated. John saw things that were wrong, showed and demonstrated them to me, talked about it, quoted other golfers and instructors, and gave me some drills. And the outcome was the same—I got a bit of a better feel for a particular mechanic, was inconsistent on the course, became frustrated, and gradually the slice reappeared.

Now, I’ll confess that John is a bit of a composite of several instructors I’ve seen, and that I’m taking the worst of these lessons and concentrating them into a couple of scenes for illustrative purposes. Still, the heart and soul of these descriptions is accurate and common—namely, the student is left feeling flawed, daunted by the work needed to get fixed, and in secret awe of the instructor’s knowledge, wisdom and skill. Like most teachers, John attempted to address the question, “how can I fix what I’m doing wrong” but not the question “how can I become more aware of what I’m feeling during the swing that might correspond to clearly inefficient mechanics?” The first question gives authority to the teacher, the “swing doctor” whose job it is to correct the student; the second question can only be answered by an exploration of the student’s experience. The answer to the first question is a should—I should be staying more behind the ball—while the answer to the second question might be a heightened awareness of some part of the swing, club, or ball or, more important, of the startling degree to which many of these realities are, in fact, invisible to me. The first outcome fuels the “golf tips” industry, generating a constant demand for ways to fix what’s broken; the second is the only way that learning and self-correction can actually occur.

John had a lot to teach me. He understood the aerodynamics of a powerful golf swing and could see the ways my swing mechanics made such a swing impossible. The problem was that his observations weren’t persuasively linked to my internal experience. In the current culture of golf, neither he nor I are supposed to be interested in that experience, but only in what I’m doing right or wrong. His expertise seemed beyond me. At the end of the day I was left with the feeling that he had something that I could only dream of having. One friend of mine somewhat hyperbolically (!) described his experience with his instructor this way: “I wish I could eat his brain!”

When I failed to get it, I could only blame myself, not John. He had pointed out my flaws and shown me the way. He had shown it to me on video and modeled it for me on the mat. He had even given me drills. If I didn’t integrate it quickly, it wasn’t because I hadn’t hit the requisite 1000 balls on the range, it wasn’t because I couldn’t feel exactly what I was doing while I was swinging well or poorly, and it certainly wasn’t because John was a lousy teacher. It was because my swing was screwed up and I couldn’t fix it.

Now, I don’t swing a golf club with my feelings. Clearly, my swing was objectively a weak and inefficient one in relation to my goal of hitting a ball long and straight. And there can be great value in having an instructor show you things that you can’t see or feel yourself. But, left at that, the ultimate residue of the type of lesson I took from John was a feeling of deficiency. This type of outcome is common. “If I could only do X,” the student thinks, “then my golf swing will be fixed and I’ll finally be happy on the course.” But there are reasons I can’t do X, and John’s style of teaching can’t possibly help me divine them. For example, if I can’t reliably feel whether my clubhead is open or closed at the top, or if my club is steep or laid off at the top, then how can my swing path and release be reliable? At best I will make last minute corrections and compensations in ways that occasionally produce a good outcome, but consistency will remain an impossible dream. And if I “fix” my alignment at the top but can’t feel the subtleties of difference, the various distinctions among different angles, then what’s the chance that I can make on-course corrections when that particular position gets out of whack?

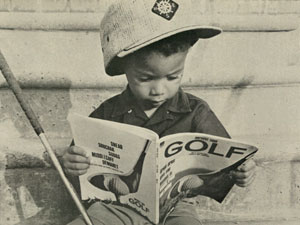

Lots of golf gurus talk about the importance of awareness, of “feel.” Most, however, don’t make it the focus of their instruction. The better ones do exactly that. I recently spent 3 days with golf instructor Fred Shoemaker at his Extraordinary Golf Program. Fred’s approach is primarily about awareness. He argues that one way to differentiate a pro from an amateur golfer is that the former is aware of what is happening in his body, club shaft, clubhead, and relationship to the target during the entire swing while, for the amateur, much of this is actually invisible. The pro takes solid contact for granted; the amateur relies on a hope and a prayer. To the extent that someone can notice fine distinctions in such qualities as balance, center of gravity, clubhead, swing path, and connectedness to target, that person will be able to internalize a powerful and efficient swing. If you can’t feel it, you can’t reliably “fix” it.

Unfortunately, even the use of the word “fix” locates golf teaching and learning in the wrong conversation. My golf swing isn’t broken. In fact, it’s perfectly designed to do certain things well—like make contact with the ball. The amateur’s swing mechanics have the implicit goal of making ball contact. If the goal, however, is a target “out there,” this swing is terribly inefficient. Shoemaker proves this by filming his students throwing a golf club out to a spot on the driving range 50 yards away. There is no ball, only a target. The results are startling at first—these swings look like a professional’s swing. Students look at the video dumbfounded. Then he asks that student to hit a ball. Immediately the old swing reappears. It looks like another species, losing its lag early—the classic amateur swing fault. The difference is that the swing without the ball is shaped by the intention and focus on a target; the swing with the ball is shaped by an unconscious focus on making contact with the ball. This latter swing isn’t “broken” and in need of repair at all. The amateur unconsciously worries about hitting the ball and adapts his or her swing to efficiently do so. The professional is hardly aware of the ball and, instead, swings in a way adapted to getting something to a target. What’s in need of changing is the intention, the awareness, the consciousness that lies behind the swing.

The only way to do this is to pay attention to our consciousness, to the consistency and clarity of our intentions, and to all their accompanying sensations involving our bodies, balance, clubhead, and swing path. Doing so over and over, without judgment, without investment in what’s right or wrong, good or bad, until the distinctions become clear—this is how people can develop a powerful and efficient swing capable of constant self-correction. Great athletes have an extraordinary capacity for self-awareness. They feel things that I don’t. Tiger Woods can shape shots on the course because he can feel and visualize them at a level I can’t. His legendary “feel” around the greens stems from the thousands of hours of practice honing his heightened proprioceptive awareness, his ability to creatively visualize, his ability to integrate stimuli from his body, hands, and senses to which he is more highly attuned than I probably ever will be.

Thus, when the headline on the cover of Golf Digest screams, “Tiger’s (fill in the name of the Golfer du Jour) 3 moves Guaranteed to Get you Up-and Down, I eagerly read it hoping that by physically copying that pro, I can be become more like him, only to find that simulating a swing mechanic without deepening my awareness of its nuances rarely leads to permanent learning. And yet, afflicted with story about my swing being broken, defective, and bad, I am in a state of permanent longing for a cure, some technique that will fix me and made me a good golfer, even a good person.