Golf seems like such a good idea, doesn’t it? It shouldn’t be the nightmare it is for so many people. Spending the morning with your friends, beautiful surroundings, playing and competing, occasionally making contact with the ball so sweet you can hardly feel it, but can only marvel at the sight of the ball doing exactly what you want it to do. No wonder so many people play it.

Therefore, it’s puzzling that more people have been leaving the sport than picking it up. It’s estimated that, in 2013, 4.1 million more people quit golf than began to play it. Moreover, within each golfer this approach/avoidance tension exists as well. Too many of us have God on one shoulder and the Devil on the other. And most golfers don’t know why.

I’m one of them. I’ve been playing for 13 years. Although my game has waxed and waned, the reality is that my scores are pretty much the same now that they were 10 years ago. And I’ve taken dozens of lessons. I shot in the low 90, sometimes the upper 80s, too often the mid to high nineties, occasionally breaking the century mark, just as occasionally getting into the low or mid 80s. Am I unusual? I don’t think so. The average male golfer in the United States shoots in the mid – 90s. Further, most people don’t get much better at golf over time—a few strokes here or there but nothing significant. At a conference of golf teachers and professionals, golf guru Fred Shoemaker asked if the teachers in the audience had seen their students get significantly better over the last 10 years. No one raised his or her hand.

I Can’t Enjoy Myself If I’m Not Playing Well

While interesting, this fact might be insignificant if most people consistently felt joy in playing. In that case, who would care? I enjoy running. I occasionally run a 10k road race. My time gets a little better but I’m never even close to the front of the pack. I don’t care. I play the guitar a little, picking out songs to sing while strumming basic chords. I love it. I know I’m not particularly good. I don’t care. The problem is that when it comes to golf, we do care, and we care in a way too often devoid of joy. We get frustrated with our performance. I have a friend who says, “I can’t enjoy myself if I’m not playing well.” When we hit the ball thin, fat, top it, skull it, chunk it, sky it, slice it, hook it, or shank it, most of us get upset with ourselves.

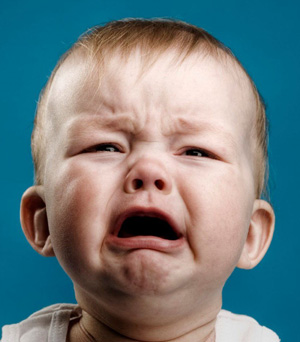

If you claim that you don’t, you’re brain dead or lying. I don’t believe you. I’ve seen it too often in myself and others. Shoemaker once said that the amateur golfer is three consecutive bad shots away from madness. “Let’s say you chunk a fairway iron and the ball scoots 25 yards,” Shoemaker said. “You feel frustrated with yourself, but brush it off and swing again. You then hit another one, equally bad. Suddenly, storm clouds begin to swirl in your mind, your mood darkens, despair beckons. Now, let’s say you swing again with the same bad result. Suddenly, in that moment, the sky falls. You’re helpless in a harsh and unforgiving universe, filled with self-hatred. The rest of the round is ruined, and a fun day has become a grim tale of survival.” Three bad shots—in actuality less than 20% of the bad shots you’ll likely hit that day—have transported you into hell.

If you claim that you don’t, you’re brain dead or lying. I don’t believe you. I’ve seen it too often in myself and others. Shoemaker once said that the amateur golfer is three consecutive bad shots away from madness. “Let’s say you chunk a fairway iron and the ball scoots 25 yards,” Shoemaker said. “You feel frustrated with yourself, but brush it off and swing again. You then hit another one, equally bad. Suddenly, storm clouds begin to swirl in your mind, your mood darkens, despair beckons. Now, let’s say you swing again with the same bad result. Suddenly, in that moment, the sky falls. You’re helpless in a harsh and unforgiving universe, filled with self-hatred. The rest of the round is ruined, and a fun day has become a grim tale of survival.” Three bad shots—in actuality less than 20% of the bad shots you’ll likely hit that day—have transported you into hell.

Melodramatic? Perhaps a little. But most readers know what I’m talking about. If all non-human sound were to suddenly cease on a typical public course on a typical Saturday afternoon, and one’s hearing were good enough, male voices shouting “F… me!,” “I suck!,” or “Take off your panties and putt it!” would punctuate the silence. And if one’s vision were equally good, one would see faces periodically contorted in rage, shoulders sagging in dejection, clubs furiously shoved back into the bag, stomping, thin and tight smiles desperately covering imploding self-esteem, heads hung low—all part of the choreography of failure on the golf course.

Frustration and Self-Loathing are Irrational

This column is going to take dead aim at the frustration, despair, and self-loathing that visits too many golfers while they play a game that should be such a source of joy and fulfillment. Let’s start by being rational. It’s absurd, ridiculous, ludicrous, irrational, unreasonable, and just plain silly for someone with an 16 handicap to get upset about hitting a ball out of bounds, or failing to get out of a bunker, or three-putting a green. I mean, professional golfers don’t get especially frustrated when these things happen, and yet amateurs (like me) act like a law of nature has been outrageously violated. Take one statistic. On a relatively flat green, 50 % of professional golfers make putts from within 9 feet. Amateur golfers have to get within 3 feet in order to have a similar success rate. And yet, looks of dejection and shock regularly appear on their faces when they miss putts of almost any length.

Or take the choice of tees from which amateurs choose to play. On most courses, men have an option of hitting from 4 sets of tees—gold (so-called “senior” tees), white, blue and black (so-called professional tees or “the tips”). There are even shorter tees of course—namely the red or women’s tees. But for a man to play from such tees is unthinkable—he might as well hand in his gender card. So, most men, regardless of their handicap, choose to play from the white or blue tees. Now, despite his claims to the contrary, a 17-handicap male golfer averages about 200 yards per drive. That means that on most par 4s, such a golfer in question will face a second shot of somewhere between 160 and 220 yards, if he’s on the fairway (a big “if,” since less than 50% of his drives will be there), the likelihood of getting onto the green “in regulation” is extremely small. The worst golfers on the PGA tour put their ball on the green from this distance 70% of the time. Our amateur’s short game is relatively poor, so his third shot at best will get him somewhere onto the green from which he will invariably 2 or 3 putt. These are statistical truths. And yet this same golfer will get intensely frustrated—indeed, even outraged–if he double bogeys.

Of course, the obvious solution of playing the forward men’s tees is rarely chosen. It would signal weakness. It would seem like “cheating,” a type of cowardice or surrender that real men can’t tolerate. But, one has to ask—surrender to what? The answer is Reality. It’s reality that we’re afraid of facing, that we can’t tolerate, that we turn into a story of failure, shame, and emasculation.

I’m sick of it. Aren’t you?

The Difficulty We All Have Seeing Reality Clearly

We wanted to create a website that helped golfers see reality—their swings, their games, development, and their psyches–more clearly and, therefore, give themselves at least the freedom to change it more effectively. If there’s one thing I’ve learned as a psychotherapist—and I believe it applies to every aspect of life–it’s that if we can’t face the truth, we can’t change. Seeing reality clearly should be easy, but it’s not. Our perceptions are distorted by experiences of our past and wished-for experiences in our future. These experiences operate behind our backs, hiding in the fabric of “common sense” or simply in what seems normal to us. We don’t accurately experience what’s going on in our swings, our games, our minds, or our lives. For example, the average golfer has 37 putts per round. If you’re an 18 handicapper and think you ought to 2-putt every green, you not only guarantee frustration, you actually make that possibility less likely to occur. Facing our limitations doesn’t mean accepting their inevitability, but instead relaxing in the present, learning from it, and enjoying what it has to offer. That’s the only way to improve and enjoy the game at the same time.

Reacting to reality angrily is usually accompanied by feelings that we’re damaged and need to be fixed and it makes learning impossible. Paradoxically, being curious and joyful about what “is” allows us to grow and develop. Letting go of our addiction to self-improvement “tips” helps us improve. Give up expectations of greatness allows for moments of greatness.

The approach we advocate is based on understanding our minds and our swings. Without the first, golfers become addicted to the newest fad or “tip.” Without the second, golfers don’t get better. The point of understanding is to 1) let go of the stories and meanings that attach to failure and success enough to see and enjoy what is actually there, 2) experience your body, the club, the ball and target as they really are, rather than how we wish they would be, and 3) to develop an on-going mental attitude that maximally permits both our joy in the game and our improvement as a player.

Failing to Succeed

You can’t learn if you can’t fail. Sounds obvious, but this simple truth is denied every day by untold numbers of golfers who respond to mis-hits and high scores as if a jury has just returned a guilty verdict. And in a sense, they’re correct—but the jury is in their heads. For too many golfers, failure is the crime and misery the punishment.

Thousands of books and articles have been written about the psychology of learning and performance. It’s axiomatic that acquiring a skill requires practice—lots of practice. And not just any practice, but practice doing the right thing in the right way. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell describes the “10,000 rule”—that it takes 10,000 intentional repetitions of a skill in order to become an expert. Butch Harmon once began a lecture to teaching pros by having someone bring up ten large buckets of balls to the stage. He said that this was what Tiger Woods hit every day when working on a major swing change. Furthermore, the balls he hit were under supervision and, thus, feedback was constantly provided. And, finally, when Tiger had mastered the basic mechanics of his new swing, Harmon created “pressure” situations in which Tiger had to repeat what he was working on (Harmon bet him $100 per shot that Tiger wouldn’t be able to use his new swing to make certain types of shots to different distances). Harmon called this “learning at the molecular level.”

In contrast, after the last lesson I took, I went to a stall and hit 20 balls on my own to “groove” my new swing. When I then went to the course and couldn’t execute it, I despaired. Do any readers out there recognize this pattern? Is anyone else sick of it? Learning takes practice, but, more than that, its success requires a particular relationship to failure. I personally hate failure. So do most people. Somehow, though, we all end up acquiring skills anyway. When I took up the saxophone in 6th grade, the shrill squeaks I produced sent our cats fleeing the house in terror. When I learned to type (in the days before computers), I spent more time with Liquid Paper than I did hitting the keys. Yet I can play the saxophone and type pretty well today. Because I persisted.

What, then, determines persistence? Persistence depends on both the value of the goal and the capacity to tolerate failure. Watch children learn how to walk. At first they look like little wobbly Frankensteins, legs wide, stepping forward tentatively with high steps and flat feet. Gradually, they cease thinking about it. They become walkers. But in the meantime they fall—repeatedly. They protest, sometimes cry, but always get up and resume their march toward becoming a “walker.” They persist. They have to – the desire to walk is hard-wired into their brains. They need to walk. The goal is all-important and no amount of frustration or “failure” can change that.

What, then, determines persistence? Persistence depends on both the value of the goal and the capacity to tolerate failure. Watch children learn how to walk. At first they look like little wobbly Frankensteins, legs wide, stepping forward tentatively with high steps and flat feet. Gradually, they cease thinking about it. They become walkers. But in the meantime they fall—repeatedly. They protest, sometimes cry, but always get up and resume their march toward becoming a “walker.” They persist. They have to – the desire to walk is hard-wired into their brains. They need to walk. The goal is all-important and no amount of frustration or “failure” can change that.

It’s different, however, when these same children attempt to master something that isn’t a biological imperative, when the goal isn’t necessarily a matter of life and death (e.g. assembling Legos). In these cases, when faced with frustration, some will break down in helpless protest, others will simply give it up entirely, while still others will tolerate their failures and gradually master the skill. Why can some kids persevere in their learning and others can’t?

Why Some Golfers Tolerate Failure Better Than Others

Golfers should be asking the same question. Why can some of us tolerate frustration on the course more than others? Some golfers will tolerate their failures enough to learn and grow, while others will either slam their clubs in angry protest, slide into despair, and sometimes even put away their clubs for good.

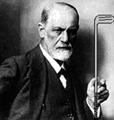

If we really want to understand the deepest sources of these reactions and the reasons that some of us can cope with them better than others, we have to look into the unconscious as well as the conscious mind. The reason is that the reactions of golfers are simply not rational. Getting upset about a game isn’t rational. Hating yourself for missing a shot that you’ve missed countless times in the past isn’t rational. Mood swings triggered by success and failure on a golf course don’t make sense. Therefore, the conscious mind can’t hold the answer. The explanation has to lie, instead, in the unconscious mind–that part of our thinking and feeling about which we’re not aware and only catch on to after the fact.

Now, as psychoanalysts, investigating the unconscious mind is our bread and butter. But such an investigation doesn’t mean that we have to blame our parents or revisit our toilet training. It does mean that we have to face the fact that our attitudes about success and failure, competition, physical competence and prowess (or the lack thereof), and learning in all its many forms are powerfully influenced by patterns and beliefs deep within our selves about which we have at best only a partial understanding. We need to reflect more deeply. We need to make the unconscious more conscious if we can.

Fortunately, our work as psychotherapists has enabled us to do so. We’ve been able to get a peek into the minds of dozens of athletes, including swimmers, runners, golfers, and wannabe-athletes like myself. At the core of the issue of coping with failure is a concept that psychologists call narcissism. Unlike its more popular usage, as in “you narcissistic self-centered sonuvabitch,” the real meaning of narcissism is the self-regard or self-love with which we invest both our personal and physical selves. It follows that there is healthy narcissism and unhealthy narcissism. If our investment is unrealistically high, we become obnoxiously grandiose; if it’s too little, we become self-hating and depressed. In order to enjoy both learning and playing golf, we have to have the right balance of narcissism.

Our Bodies Should Do Exactly What We Want Them to Do

In the earliest years of our growing up, our narcissism is especially focused on our bodies. When our bodies are working well, we feel good; when they don’t, we feel bad. “Working well” means they do what we want them to do, what we intend for them to do. Notice the sheer joy of a child running across a field. It’s as if the body’s movement itself is the real source of pleasure. Then notice the frustration of a child unable to make his or her body work properly, say when unsuccessfully trying to climb steps. The body’s physical limitation becomes a painful outrage.

This investment—this narcissistic investment—in our bodies continues throughout our lives. At the heart of the frustration and despair of aging is the awareness that our bodies can no longer do what our minds tell them to do. For example, I have a picture in my mind of playing basketball and running a fast break down the court, my 17-year-old body fluidly and effortlessly soaring to the basket for an easy layup. The last time I tried to make my body—my 55-year-old body–do the same thing, the result was a strained hamstring, a missed shot, lungs gasping for air, and the depressing recognition that I was one of those old guys trying to deny that fact.

This discrepancy between the image of what our bodies should do and what they actually do lies at the heart of the golfer’s frustration. We have an intention to hit the ball. Sometimes we even have a picture in our minds of exactly how we’re going to do it, including how our bodies will move, what contact will feel like, and what the ball will do as a result. The ball is just sitting there, waiting. We’ve done it before; we can do it again. It’s like me visualizing that layup. But then….thud!… the club hits the ground before the ball. The resistance of the earth sends vibrations up our arms, a feeble amount of energy is imparted to the ball which lurches forward with pitiful speed and distance, dirt flying, leaving a divot the size of the Mariana trench. Or, equally bad, we hit the ball thin, a stinger. No, not the type that Tiger Woods hits with his 3-wood or 2-iron on tight fairways but the type that causes stinging pain that begins in the hands and quickly shoots up the arms like an electric current. The ball shoots forward 10 feet above the ground, slicing with so much side spin that, were there no obstacles or gravity, there’s a good chance it would complete a 360 degree earth orbit and come back to its original resting place at our feet.

The failure to execute our intentions, the disconnection between our bodies and imaginations, puts us into the same psychic space as that child falling down, that boy producing squeaks on his saxophone, or that 55 year old man pulling a hamstring going to the hoop. That space is one in which our narcissism takes a beating.

We React to Frustrations With Judgments and Stories

When an intention fails or a wish is thwarted, frustration is a normal instinctive response. But human beings are not only creatures of instinct; we’re also creatures that make meaning. When our bodies let us down we react with a story to help us make sense of the helplessness inherent in that experience. We might make a judgment about our faulty mechanics (a judgment, by the way, that research shows is almost always wrong). We might also unconsciously decide that it was an “accident,” a freak of nature, an indictment of our golf instructor, a sign that we’re tired, a result of feeling rushed or of waiting too long for the foursome ahead of us, a failure, a sign of weakness, an expression of incompetence, personal failure, or just basic badness in the very core of our selves. These stories appear in a nanosecond, often barely reaching awareness. They might hide behind feelings of irritation, a slump in our energy, a deflation of our mood. But they’re definitely stories and each of us have characteristic ones that we tell ourselves when we encounter an obstacle we can’t magically eliminate.

One golfer I saw in therapy used to tell me that when he hit poor shots he’d feel angry with himself, and admitted to occasionally slamming a club. “I know what I’m doing wrong but just can’t stop it,” he complained. “I feel like shit and hate myself when I can’t hit a simple pitch to a green.” His “story” was that his golf swing was the same as his self—bad swing, bad self. Another patient told me that when he was on the golf course he sometimes worried that there might be something physically wrong with him. He was 6’ 3” tall and quite fit, but he could only hit a drive 220 yards while men half his size frequently out-drove him. His story was that his body was somehow intrinsically weak and incompetent. In both cases, there were ample reasons in their personal histories for such stories to now present themselves. Nevertheless, they were stories; they felt real but weren’t.

Managing Toxic Feelings of Helplessness on the Golf Course

The most important stories we tell ourselves often involve attempts to manage feelings of helplessness. Helplessness is one of the most toxic of human emotions. We can’t and don’t let ourselves feel it in pure form for very long. The worst reactions we have on the golf course involve stories intended to explain away the discrepancy between a wished-for and actual reality, a discrepancy about which we feel helpless. Such feelings are easy to understand because we usually can’t accurately account for what happens in a swing that produces a poor outcome. Fred Shoemaker argues that, for the amateur golfer, most of what is actually happening in the golf swing is invisible, outside awareness. A trivial example: An amateur golfer is asked to take his club all the way back and to report how close it is to level. Every single time, the amateur’s report is incorrect. He’s then asked if his clubhead is open, closed, or neutral. Again, his answer is almost always wrong. It is impossible to have a consistent and repeatable swing when its length and the position of the clubhead is functionally invisible to the swinger.

The most important stories we tell ourselves often involve attempts to manage feelings of helplessness. Helplessness is one of the most toxic of human emotions. We can’t and don’t let ourselves feel it in pure form for very long. The worst reactions we have on the golf course involve stories intended to explain away the discrepancy between a wished-for and actual reality, a discrepancy about which we feel helpless. Such feelings are easy to understand because we usually can’t accurately account for what happens in a swing that produces a poor outcome. Fred Shoemaker argues that, for the amateur golfer, most of what is actually happening in the golf swing is invisible, outside awareness. A trivial example: An amateur golfer is asked to take his club all the way back and to report how close it is to level. Every single time, the amateur’s report is incorrect. He’s then asked if his clubhead is open, closed, or neutral. Again, his answer is almost always wrong. It is impossible to have a consistent and repeatable swing when its length and the position of the clubhead is functionally invisible to the swinger.

It is this invisibility that generates our lack of consistency and, as a result, our feeling of helplessness. In my work as a psychotherapist, I often tell patients that if they don’t understand their psyches, then their psyches will always feel out of control. Similarly, since we can’t really let ourselves fully see and experience what’s going on in our golf swings, we will always be prone to feel helpless in relation to their outcomes.

Helplessness is always difficult to tolerate. Children, obviously, spend a great deal of time coping with it. Kids who are terrified by violence in their environment, for example, often deal with their fear by becoming violent themselves. This near-universal phenomenon is nothing more than an attempt to evade the feeling of helplessness. Other times we spin a tale to ourselves that we aren’t really helpless—we’re just getting what we deserve. Self-blame is another common childhood strategy to avoid feeling the helplessness that children feel in relation to a tyrannical or abusive parent. Better to think that the abuse was deserved and fair than to accept that it was outside our control. And, of course, rage itself is one of the most common responses to helplessness. Anger is an energetic protest against helplessness, containing in it a furious refusal to accept a loss of control. We rage against our fate, our failures, our selves, and our bodies rather than truly face—with compassion and curiosity– the ways in which we are thwarted by our own imperfections.

Of course, there are other, healthier ways to cope with helplessness. We see them all the time. Mastering anything requires the ability to tolerate failing long enough to improve. This process has been so woven into everyday life since infancy that we hardly notice it. Whether it’s learning how to drink from a cup, use a spoon, jump rope, throw a ball, write with a pencil, drive a car, or waltz, we’re wired and encouraged to tolerate the “error” part of trial-and-error learning enough to develop mastery.

A friend of mine described how she realized, in the midst of her LPGA career, that her distance control with her wedges was poor and determined to correct it during that off-season. Hitting wedges became 80% of her practice schedule. She hit thousands of balls with her wedges to different distances. She didn’t experience her difficulty as shameful or as an outrage. She wasn’t angry when she couldn’t at first dial in her distances. Instead, she simply attempted to increase her awareness of what she was doing—how far she took each club back, the angle of attack, ball position, and the precise yardage that resulted. It wasn’t tremendously frustrating to her because she was determined to master it, had the confidence that eventually she would, and put in the time to do so. Her problems with pitching didn’t mean anything to her about her self. They were simply an obstacle to the end of what did mean a lot—becoming the best golfer she could possibly be.

Coping With and Appreciating Reality in Golf

Another way to describe the process of tolerating errors, failure, or the moments of helplessness inherent to both, is that we learn to cope with and appreciate reality. As children, our narcissism is often of the grandiose variety. We feel that we can and should control everything and everyone, our own bodies and those of people around us. This grandiosity gets regularly shattered when we encounter the limits of our wills, our wishes, and our bodies. Then we rage against this powerless state and attempt to regain control. Gradually, we learn. We learn that we’re neither omnipotent nor truly helpless. We develop real skills and competencies that help us get what we want without having to resort to magical flights of fancy or crash-landing in defeat.

Obviously, it’s crucial how the world around us, the human world, reacts. Families, peers, and teachers can either help us tolerate frustration or increase it. They can either help buoy us up while we’re wrestling with incompetence or they can deflate us. They can provide incentives to hang in there or shame us for not being good enough. Some children, of course, are born with temperaments that are more resilient and less vulnerable to frustration. Still, the social environment in which children learn continues to be a powerful determinant of the development of the confidence necessary to risk failure and grow.

Child development experts devised an experiment called “the visual cliff” to demonstrate this finding. A table is covered by a piece of clear glass long enough to extend 2 feet over one end. A 6-month-old baby is put on the table and encouraged to crawl to the end of it. Her eyes tell her that the table ends, and that to continue, therefore, is to fall off the “cliff.” Her tactile senses suggest that it’s safe. What determines whether the baby has the confidence to risk continuing? Researchers found that it was the response of the environment. If the baby’s mother stands at the end of the glass, happily and confidently encouraging the baby to risk it, she will. If the mother looks worried or isn’t paying attention, the baby stops and refuses to advance.

Thus, the degree of patience and frustration tolerance that we each have when it comes to mastering a difficult skill has something to do with the ways our past environments either nurtured or inhibited our capacities to learn, how they reacted to failure, and how realistic their expectations were about the probability of our success. For example, a family that reacts negatively to a 4 year old child’s failure to master the use of a knife and fork sets up in the child an unreasonably negative attitude toward learning. Similarly, a family that expects too little and, say, praises a ten year old child for the same thing sets the bar so low the child doesn’t develop the discipline and motivation for taking on hard challenges.

When I was growing up, my father used to enjoy competing with me. When I was as young as 9, he’d take me out bowling and howl in delight when I threw gutter balls. When I first entered adolescence, he’d provoke arguments about things he knew a lot about. I grew up feeling ashamed of losing contests in which I should never have been involved. I felt that I’d “failed” at tasks that were unrealistic to begin with, and that I’d lost competitions that I never had a chance of winning. Winning and losing were ever-present, highly charged, and high-stakes propositions. It was no wonder that when I took up and fell in love with golf, that learning process was complicated and that the stories I’d unconsciously learned about success and failure were going to rear their heads on the course.

And they did. I encountered the range of demons with which most amateur golfers are familiar—frustration, anger, despair, and self-condemnation—along with the highs and pleasures of the game. But I was aware that these demons didn’t have to do with the game; they had to do with me. They had to do with my expectations of myself and the complicated and sometimes tormented ways I reacted to helplessness and failure, ways that I had come by honestly—that we all come by honestly—during the course of growing up.

Some people have told me that I’m making golf too complicated, that I spend too much time in my head. I couldn’t agree more. But I’d argue that we all complicate our golf games with stuff that comes from our heads, that we can’t help but do so, and that the only important question is how much we’re aware of it and how we relate to it. Because the fact is that we’re creating thoughts, feelings, and stories about our selves all the time on the golf course. We can’t help it. It’s what human beings do. Usually however, these are outside our awareness, shaping our experience from the wings. Learning how to bring them onto the stage, in the bright lights of awareness, will only lessen their power to direct us and, instead, open up the space to experience greater joy and freedom doing something—playing golf—that we truly love.

When I first started learning to play, and was playing REALLY badly, I would descend into horribly black moods. No one knew it but me, thankfully, but it was pretty dark in there. I grew up in a highly critical environment (at times, well beyond critical — but that’s a story for another day). As a consequence, I believe, I am (or was) a perfectionist. This is a great quality for a computer programmer. Computers do not deal well with imperfection. This is a terrible attribute in a golfer.

It took years, literally, to overcome this. And I believe the learning carried over into other areas of my life and made me a much happier person. I owe a lot to golf, and to the dear friend who brought me back into the game over 20 years ago.

One of my friend’s favorite “teachings” was, “Everybody is just making it all up.” I have wondered, since his passing, if he realized how literally true this statement is. Human beings are the true “virtual reality” machines, as everything we perceive is a construct in our brain. And what tiny, imperfect, incomplete constructs these are!

So, I was making up some really bad shit around golf. Sure, I still get frustrated. Sometimes angry. But those black moods are gone and I cannot express how thankful I am for that.

I still wish I could have made the Champions Tour. I think I had about 5 years to prepare, and so I indulged the fantasy until I could no longer cling to it and still claim to be sane.

Now, however, my goal for each round is to ascend into what I call “The Zone of Indifference” and to laugh at my mistakes and ineptitude. And when I can reach this zone, better play always results. And a lot more fun!